By Lyra Fontaine

Researchers from UW Mechanical Engineering (ME) and UW Medicine have developed a solution to help surgeons perform safer, more complete and more precise endoscopic procedures in the sinus and skull.

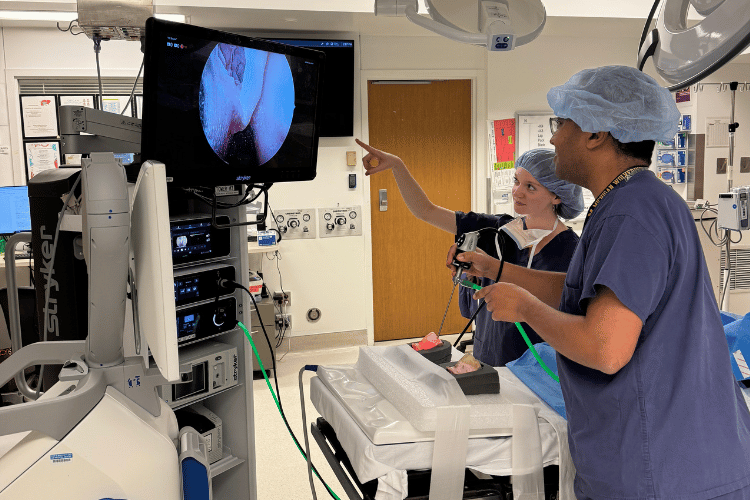

ME Ph.D. candidate Nicole Gunderson and Dr. Waleed Abuzeid, UW Medical Center rhinologist and ENT-otolaryngologist, conducting an endoscopic survey of a 3D-printed sinus model to check the completeness of the surgery they performed on it. Photo provided by Gunderson.

This could serve the one in eight adults who suffer from chronic rhinosinusitis, a disease of the areas within a bone between the eyes and behind the nose bridge. These cavities are made up of honeycomb-like structures that can become inflamed or contain diseases that surgeons can remove. To avoid hitting critical structures near the cavities, surgeons often leave behind tissue, and 30% of the surgeries need to be repeated.

To reduce the rate of repeat surgeries, clinicians need an accurate guide for these procedures.

The UW-developed VISTA (vision-integrated surgical tracking assistance) system can provide much-needed guidance by creating 3D models of the surgical field as tissue is being taken out. The models are then used to update medical imaging taken before surgeries to show surgeons how much tissue has been removed and to quantify how close their medical tools are to critical structures such as the eye and brain.

“VISTA could create a huge impact for patients and the people paying for image-guided surgery, including sinus and skull-based procedures,” says ME third-year Ph.D. student Nicole Gunderson, who leads engineering development for the project. “I’m proud to be one of the people working on it.”

After senior faculty donated their time and money in the project’s early stages, the student team secured their own funding for ongoing research. They won second-place in the Holloman Health Innovation Challenge and received funding from the Washington Research Foundation for phase 1 technology commercialization.

Gunderson works on the project with UW Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery residents Jeremy Ruthberg, MD, and Graham Harris; fourth-year ME Ph.D. student Pengcheng (Pearson) Chen; and neuroscience and computer science undergraduate student Di Mao.

“The students have shown exceptional skills in advancing the state-of-the-art in 3D endoscopic video reconstruction while playing key roles in driving this multidisciplinary project forward, working hand-in-hand with surgeons,” says ME Research Professor Eric Seibel, the principal investigator for the project who advises Chen and Gunderson, and co-advises Ruthberg.

Other advisors and lead researchers include Randall Bly, MD, an associate professor of Otolaryngology at the UW and a pediatric otolaryngologist at Seattle Children’s; and Waleed Abuzeid, an associate professor of otolaryngology at the UW.

An accessible solution

ME Research Professor Eric Seibel, ME Ph.D. Nicole Gunderson, UW Medical Center resident otolaryngology physician Jeremy Ruthberg, and ME Ph.D. candidate Pengcheng (Pearson) Chen after accepting their second-place award at the Holloman Health Innovation Challenge.

Surgeons use an endoscope — a device with a light, small camera at the end of a long, flexible tube — in some minimally invasive surgeries to inspect the inside of the body. It can be challenging to completely remove all the diseased tissues with endoscopic surgery because of limited camera views and the pre-surgery CT scan not representing the current state of the surgical scene.

“I was shocked by the rates of inaccurate surgeries and revision surgeries that some patients undergo because of the inadequacy and the inaccessibility of currently used technologies,” Gunderson says. “A second procedure is a big deal for kids undergoing pediatric surgery and for the people paying for it.”

She adds that pairing a standard endoscope with VISTA could provide tracking that is safer, more accurate and more accessible.

Gunderson and Chen developed the methods behind creating the 3D models, reaching a breakthrough when they found a way to model depth with a standard, one-camera endoscope through two slightly offset 2D images.

“We simulated how humans perceive depth with our eyes,” Gunderson says.

Our brains are able to determine the depth from our eyes to different objects in our environment by calculating the distance between our two pupils and the focal length of our eyes, comparing the slightly offset images from each eye.

A type of endoscope called a stereoscope, which has two lenses built in, can replicate this process. However, creating a version of depth estimation that simulates stereoscopy using a single-lensed endoscope is a difficult computational problem.

In the VISTA system, a computational process reconstructs a 3D scene from a series of video frames, generating optimized views of the image. An algorithm built by the researchers then generates 3D depth by synthesizing two camera viewpoints from different angles. Using the synthesized viewpoints, 3D reconstructions of the live surgical scene can be generated, displaying updated models of anatomy as surgery progresses. These models are quantifiably accurate, allowing surgeons to measure the completeness of the procedure and their live distance to various anatomical structures.

Existing electromagnetic systems can track endoscopes during surgery. But with 2 mm of error, they can be inaccurate and only accessible in certain hospitals. In addition, these tracking tools add an additional cost to the surgery and can be accessible. Tracking tools were only used in 11% of surgeries where patients were covered by Medicaid or Medicare, according to a study of endoscopic sinus surgery patients. In contrast, VISTA has demonstrated just 0.3 mm of error in 3D reconstruction accuracy and uses tools already widely available in surgical rooms, requiring less training.

It’s also more effective than a second CT scan during surgery, which would be expensive, expose patients to more radiation and wouldn’t show real-time updates.

Collaborating with clinicians

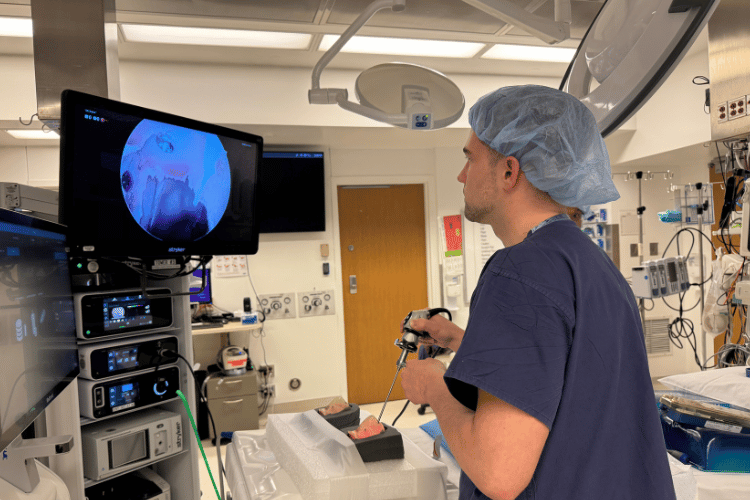

Graham Harris, a UW medical student assisting with the project, captured an endoscopic video of the 3D-printed model the team will use to create 3D reconstructions of the scene. Photo provided by Nicole Gunderson.

While Gunderson studies how to update the CT scans with 3D models, UW Medicine collaborators use clinical data to validate the models’ accuracy. The team has also studied cadavers to prove that the technology is effective in clinical models. The researchers are now validating their work in operating rooms at Seattle Children’s, where they are comparing sinus surgery videos with the VISTA 3D models.

Working with clinicians enabled the engineering team to find an ideal application for their technology.

“The collaboration with UW Medicine has been fantastic,” Gunderson says. “Once we talked to clinicians about the gap in image-guided surgery, they gave us such a clear need related to what we were doing already. Putting the clinical need first helped us advance the technology and drive commercialization.”

The researchers hold multiple patents for VISTA and related technology, underwent the UW Regional National Science Foundation Innovation Corps and have started the process of filing for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

And now they are exploring how VISTA’s 3D modeling could be used for a wider variety of image-guided surgeries, including neurosurgery.

“We are looking forward to applying our technology to look at brain tissues that move as tumors are removed,” Gunderson says. “The focus of our upcoming research is to model these deformable, dynamic structures.”

Originally published January 12, 2026